The Red Mill in Operation: 1810 – 1928

Ralph Hunt built the earliest section of this Mill to process wool sometime around 1810. His wool business failed, however, thanks to a permanent downturn in the market for domestic cloth. By 1820 Ralph confessed to the Census that “the establishment has been doing very little for two or three years past. The demand for sale of the cloths and sattinets are very dull…a few of the farmers get their wool manufactured, but from the low prices of foreign cloths.” Things did not improve and Ralph lost all of the family’s property, more than 400 acres and mills on both sides of the river. He defaulted on his mortgage, and the Taylor family took ownership.

From 1828 to 1834 John Bray and John B. Taylor took over running the Woolen Mill. The Taylors, now the dominant merchant family, changed the name of the town from Hunt’s Mills to Clinton, after the popular New York governor DeWitt Clinton. Bray and Taylor continued in the woolen business but they also diversified by grinding feed, flour and stone plaister, as well as by selling chestnut wood for rails. They even opened a dry goods establishment which carried everything from china to sheet iron. But Bray and Taylor also failed in their business, selling it for three quarters of its purchase price.

John W. Snyder, the new owner, refitted the Mill for grist and ceased wool production. But he too quickly fell into debt, and lost the property in 1842. After a swift series of owners, the Easton Bank split the site into a mill and a quarry. In 1847 the Mill was sold to John F. Stiger and John A. Young, who used it to grind flour and grist. In 1868 Young sold his part of the business to his partner, John Stiger, who continued to operate it as a grist mill.

In 1871 Stiger sold the mill and it again changed hands several times before it was purchased by Philip Gulick in 1873. Gulick ground grist on the third and fourth floors of the mill and produced peach baskets in the first level. In 1892 Gulick set up The Clinton Illuminating and Water Co. on the second floor of the mill. It provided electricity for Clinton’s street lamps. Gulick died in 1901 and his widow rented the Mill to Elmer and Chester Tomson and in 1905 they purchased it outright.

Chester changed the mill’s operation to grist to graphite and for a short time the mill became known as the “Black Mill.” The greasy black dust was wildly unpopular in town, and after a public outcry he turned to grinding talc and the Mill was soon dubbed the “White Mill.”

The talc mill was in operation day and night, with three run of stone, three elevators and one crusher. Electricity powered the lights until midnight, when six kerosene torches took over. Two storage sheds had been built between 1903 and 1912, one small in front of the mill and a larger behind. In 1928 Chester sold the mill to the Clinton Water Supply Company, and the mill ceased operations.

Today the Mill houses a large portion of the Museum’s collection. Exhibits on the 1st, 2nd, and 4th floors share a small part of the history of this building and its ever changing role within the Clinton Community.

The Mulligan Quarry: 1848-1960

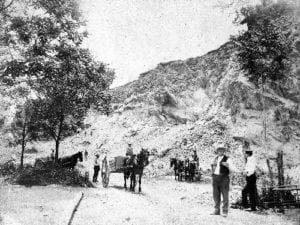

The first faint echoes of the Mulligan family were heard on Quarry Hill in 1848 when two of the four Mulligan Brothers, Frank and Pat, purchased the property from the Easton Bank for $100 dollars down. Seven years later they sold the business to J.P. Huffman who immediately resold it to local businessman George Gulick. It was from Gulick that the eldest Mulligan Brother, James, leased the quarry in 1858, continuing the business his brothers started.

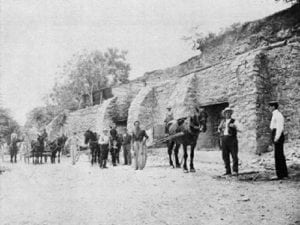

Under James’s leadership, the business ran mostly on a barter basis. He exchanged stone for everything from livestock to liquor. By 1860 James ran three lime kilns, built a two family tenant house on site, produced 25,000 bushels of lime annually, charged 10 cents per bushel and netted $2,500 in profit. James’s wife Catherine and five children soon emigrated from Ireland to Clinton. Catherine’s brothers, William and Pat, moved to Clinton as well and worked as laborers in the quarry. Other Irish immigrants were arriving in Clinton at this time. Most, like the Mulligans, settled on Halstead Street and many found occasional work at the Quarry.

When James died in 1862 the quarry business passed to his sons. His youngest son, Michael headed the company and under his leadership, the business flourished. Gone were the days of barter and instead the Mulligan brothers expected cash on the barrelhead. Within four years the brothers were able to raise enough money to put a down payment on the quarry, and it was back under Mulligan ownership. Michael soon expanded upon the seasonal quarry business first by cutting and storing ice for sale in the summer, and then with the advent of the Railroad in 1875 by selling coal during the winter season. Michael was at an advantage, in coal sales. He bartered gravel for the rail beds in exchange for cheaper rates on his coal shipments. With the arrival of the automobile, stone from the M.C. Mulligan quarry also filled the network of road beds that soon blanketed the region. The stone for the foundation of the Town Hall and Library on Main street was donated by the Mulligan brothers, and after the great fire of 1891, Mulligan stone was used to rebuild the town of Clinton.

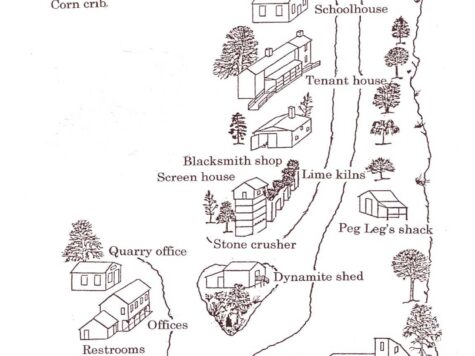

The Mulligan Quarry business was in continual operation through to the 1960s. Michael Mulligan’s Lime Kilns still stand today as do five of the early Quarry buildings including the Quarry Office, Screen House, Dynamite Shed, Blacksmith Shop and Tenant House. The stories of the Mulligans, quarrymen and tenant families help bring these buildings to life

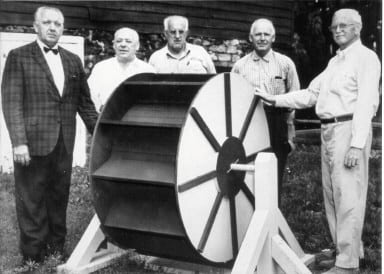

Creating the Museum: The Red Mill Five

Five community-minded men, known affectionately as the Red Mill Five, acted with vision and courage when they bought the derelict Red Mill to restore as a museum. Monroe DeMott was president of Shive, Wright and Exton, a real estate and insurance firm; Cyrus Fox owned Cyrus R. Fox, Inc. lumberyard; Ralph Howard was a restaurateur who owned and ran Clinton House; Robert Lechner was a teacher who founded and ran a camp in Stanton; and James Marsh was a well known artist and musician.

The story began in 1960, when the Red Mill Five, spearheaded by James Marsh and Monroe DeMott, finally succeeded in buying the landmark Red Mill on the west bank of the South Branch of the Raritan River for $15,000.

For the next 12 years, the Red Mill Five met at noon on Fridays at the Clinton House to turn their vision into reality. Ruth Hetherington, executive secretary to Monroe DeMott, became secretary to the Red Mill Five for 12 years and was an integral part of those formative meetings at the Clinton House.

The first three years were about the hard, hands-on, physical work as the large, empty building was cleaned and repaired, the roof and waterwheel replaced, and a collection started through donations from the local community. Dorothea Connolly was hired as Curator and she completed the first exhibits in the Mill – a kitchen exhibit and a children’s exhibit with old clothes and games. In 1963, the Clinton Historical Museum opened to the public. Following in Dorothea Connolly’s footsteps, Claire Young later became staff curator and continued to fill the Mill with exhibits, including a Victorian bedroom and parlor, a World War I living room and kitchen, and a wheelwright’s shop.

In 1964, James Marsh bought the Mulligan Quarry and donated it to the museum. The museum and grounds were officially dedicated in 1965. By 1972 the Red Mill Five were ready to pass the baton, and other community members stepped forward to continue their mission to protect the Mill, its collections and our local heritage. The museum grew and, over the years, became known as the Hunterdon Historical Museum in 1996 and, in 2002, became the Red Mill Museum Village.